I thought the previous installment from C. S. Lewis’s The Pilgrim’s Regress would be the last from that book, but now I’ve decided to not leave the book on such a stark and ugly note. Or such ugly pics, for that matter.

In that post, John faced Death–literally. Death told him that death to self is inevitable: He can go willingly or he can struggle. He chooses to go willingly.

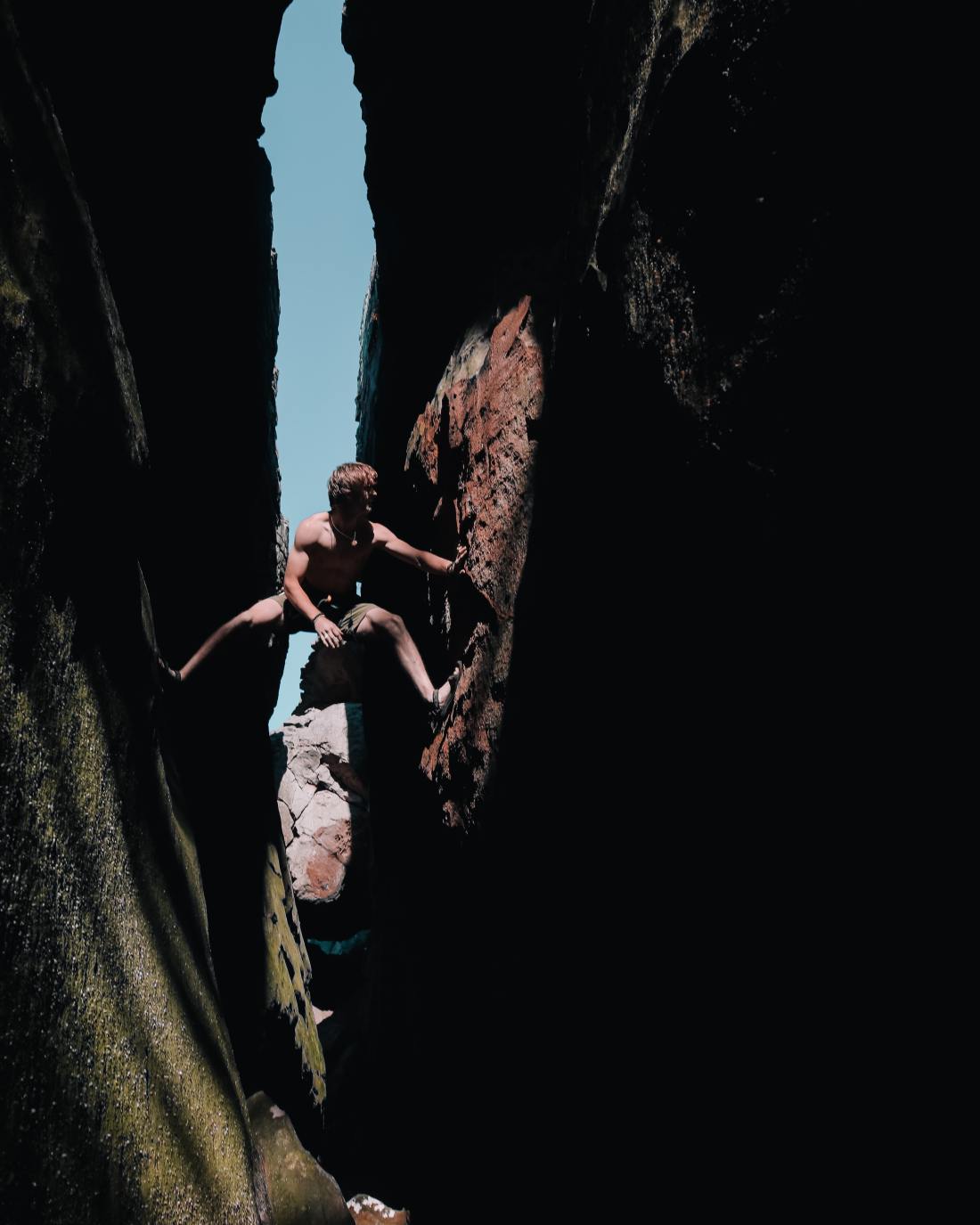

He finds himself on the floor of the canyon. A small crowd of people are standing around a figure sitting on a throne: Mother Kirk (the mother church). A large pool stretches between them and the opposite wall of the canyon. His old companion Vertue is there too, sitting on the ground completely naked. John’s long quest has reached its climax.

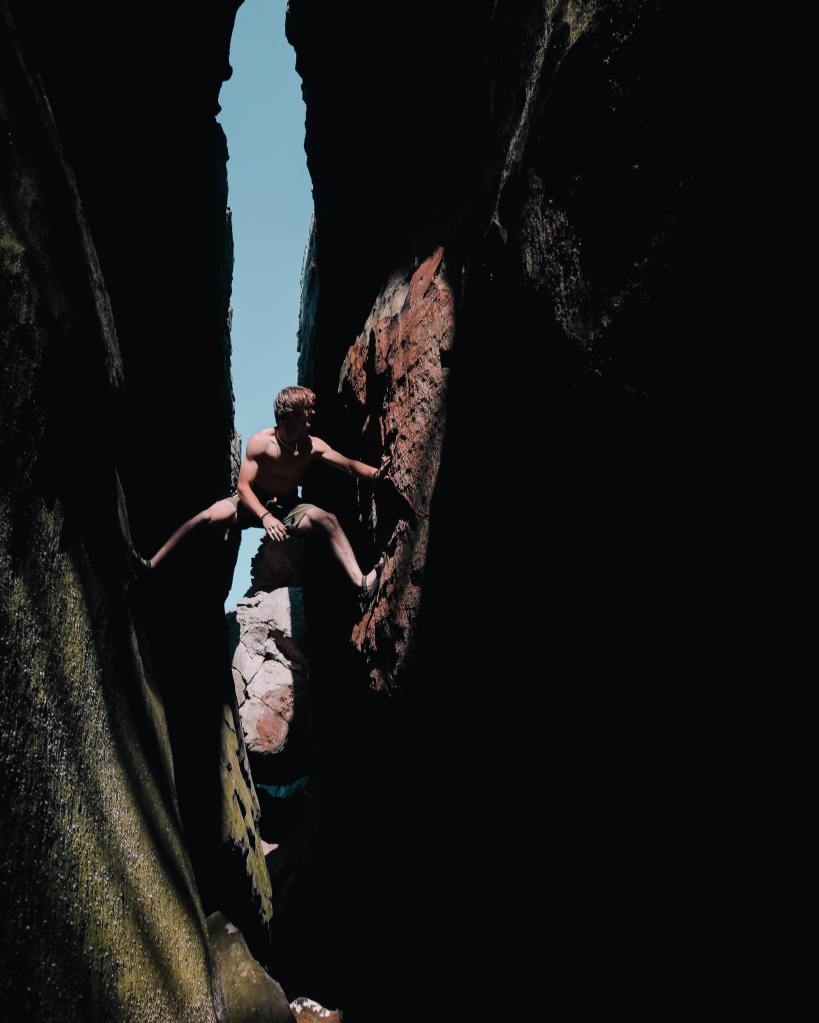

Mother Kirk tells them that the only way to the other side is to become naked like Vertue and dive into the water headfirst. Then they must swim downwards to a tunnel in the wall that leads up and onto the opposite side. John thinks to himself, “I see they have brought me here to kill me.”

As he hesitates on the brink, he is visited by wraiths of all the men representing worldviews he met heretofore, such as Old Enlightenment, Sensible, and Humanist, who all try to tempt him away from believing in the necessity or even the reality of what he is about to do (baptism and rebirth). But Vertue interrupts his ruminations: “Come on, John…the longer we look at it the less we shall like it,” and he dives into the water. John soon follows.

From The Pilgrim’s Regress by C. S. Lewis, Book 9, Chapter V: Across the Canyon

My dream grew darker so that I have a sense, but little clear memory of the things that John experienced both in the pool and in great catacombs, paved sometimes with water, sometimes with stone, and upon winding stairways in the live rocks whereby he and Vertue ascended through the inwards of the mountain to the land beyond Peccatum Adae.* He learned many mysteries in the earth and passed through many elements, dying many deaths….

Of all the people he had met in his journey only Wisdom appeared to him in the caverns, and troubled him by saying that no man could really come where he had come. All his adventures were but figurative, for no professed experience of these places could be anything other than mythology. But then another voice spoke to him from behind him, saying:

“Child, if you will, it is mythology. It is but truth, not fact: an image, not the very real. But then it is My mythology. The words of Wisdom** are also myth and metaphor: but since they do not know themselves for what they are, in them the hidden myth is master, where it should be servant: and it is but of man’s inventing.

“But this is My inventing, this is the veil under which I have chosen to appear even from the first until now. For this end I made your senses and for this end your imagination, that you might see My face and live.

“What would you have? Have you not heard among the Pagans the story of Semele? Or was there any age in any land when men did not know that corn and wine were the blood and body of a dying and yet living God?”

Afterword

This passage is unique in the book for it is the only time God Himself speaks. The voice seeks to set John’s heart at ease and counter what Wisdom said about the relation of truth and myth.

In this, his first book that was not poetry and his first apologetic, Lewis certainly had in mind the theories of The Golden Bough by Sir James George Frazer, an enormously influential series of books first published in 1890. It argued that myths of a god whose death and resurrection enabled the crops to grow–or were the crops growing–were nearly universal across cultures, and the story of Jesus was merely one of these.

What John is experiencing as he dives and goes underwater is of course baptism: death to the old self, the rising of the new. Wisdom has said this could only be metaphorical, not a real experience. But God counters that use of the word “only” and explains that it is both mythical and real, it is His means by which finite, sinful people will be able to live with a holy God, “that you might see My face and live.”

Lewis and Literary Theory

Lewis responds to Frazer’s anthropology by applying knowledge from his own areas of expertise: literary and linguistic theory and clarifying the relationship between myth, fact and revelation. “It is but truth, not fact” is a concept seeded into Lewis by his friend, J.R.R. Tolkien, during the famous chat they had on Oxford grounds which led to Lewis’s conversion. The seed Tolkien planted bloomed also into an essay Lewis later wrote, “Myth Became Fact.” It provides a distinction between myth and legend, myth and truth, myth and factuality. It describes myth in a way that no other literary analyst, as far as I know, had done. Lewis says myths are not merely legends, much less allegories, or even untrue. He says that myths allow us to experience, to “taste,” an archetypal truth that gives rise to many truths.

Lewis and Tolkien (and G.K. Chesterton as well) believed that God prepared the way for Jesus Christ through the Jews by law and prophecy and through the pagans by imagination. Stories of a dying but living god seized the pagan sensibility. There are myths that humans invent and then there is the one that God invented: All life does come only from plants that die in winter only to rise again. All plants really do provide a seed that dies yet creates a much bigger life.

Jesus himself seems to acknowledge these pagan ideas when he answers the request from the Greeks in John 12:20-25: Predicting his own death, he continues, “Very truly I tell you, unless a kernel of wheat falls to the ground and dies, it remains only a single seed. But if it dies, it produces many seeds.”

The voice of God here says that Wisdom’s words also consist of “myth and metaphor” but Wisdom is unaware that they do. This idea that literal language was not distinctly different or free from figurative language was first advanced by Giambattista Vico (1668–1744) and radicalized by Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900). But no modern literary theorists advanced it until I.A. Richards in 1936. It became a central tenet to the deconstruction theories of Jacque Derrida and Paul deMan much later in the 20th century. That Lewis was arguing it in 1933 shows he was ahead of his time.

Whither Mysticism?

What has all this to do with mystical wonder? This passage illustrates an intellectual dimension of mystical wonder. It portrays the astounding way God reaches us through all we experience as meaning. The One revealed as The Word is the essence of meaningfulness. When we want to open a door to a transcendent dimension we use myth and metaphor. When God wants to, He uses human lives.

*Latin: the sin of Adam